Externalities

Christopher Makler

Stanford University Department of Economics

Econ 50: Lecture 23

Announcement

Econ 51 next year will be offered

WINTER

FALL

Climate change is an equilibrium phenomenon.

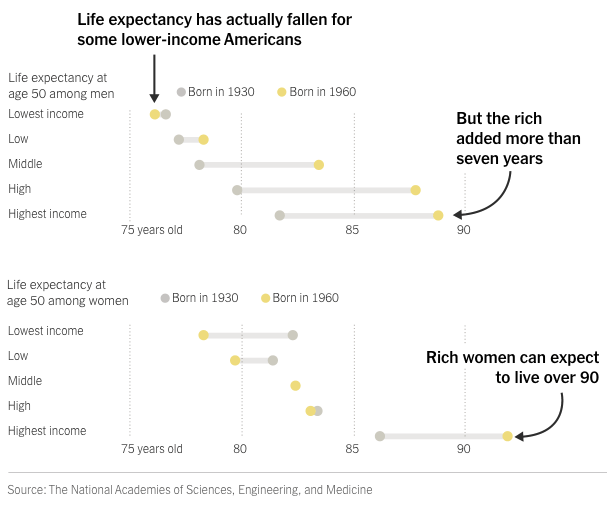

Inequality is an equilibrium phenomenon.

Housing is an equilibrium phenomenon.

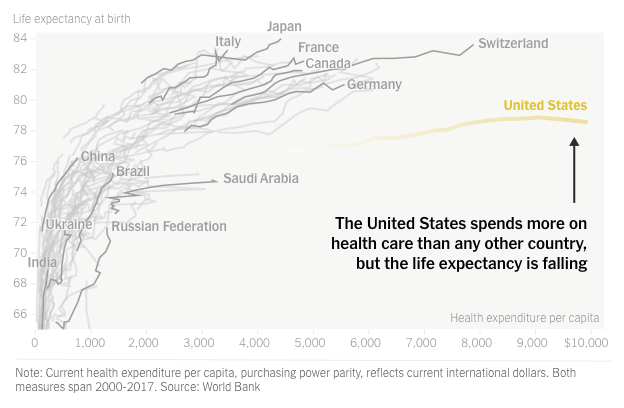

Health is an equilibrium phenomenon.

For 9 weeks, we have studied

the gravitational forces that drew systems towards equilibrium, and kept them there.

To what end, if not to find

a way to a better equilibrium?

Public Economics

Some goods are underprovided or overprovided in equilibrium.

Some goods will never be provided in equilibrium

Market equilibria occur when all agents try to maximize their own utility/profit/payoff.

These are known as market failures.

The field of public economics studies how public policy

can (usually partially) correct those failures.

EXTERNALITIES

(TODAY)

PUBLIC GOODS

(NEXT TIME)

Externalities

- Situations in which the actions of agents affect the payoffs of others

- Often caused by "missing markets"

- Markets (or more generally, everyone acting in their own self interest) will not generally solve the problems — equilibria are inefficient or inequitable

Externalities

- One agent affecting another:

- Steel mill and fishery

- Many agents affecting each other:

- Market externalities

- Tragedy of the Commons (Mon)

Externalities

- One agent affecting another:

- Steel mill and fishery

- Many agents affecting each other:

- Market externalities

- Tragedy of the Commons (Mon)

Not as much a "one size fits all" model,

but more of an approach:

- identify a "social welfare function" that tell us what the "socially optimal" outcome is

- model the incentives agents face, and understand why the "market equilibrium" outcome differs from the "socially optimal" one.

- try to find a way to adjust the incentives to achieve the socially optimal outcome

- usually involves getting the agents to internalize the externality they are causing others

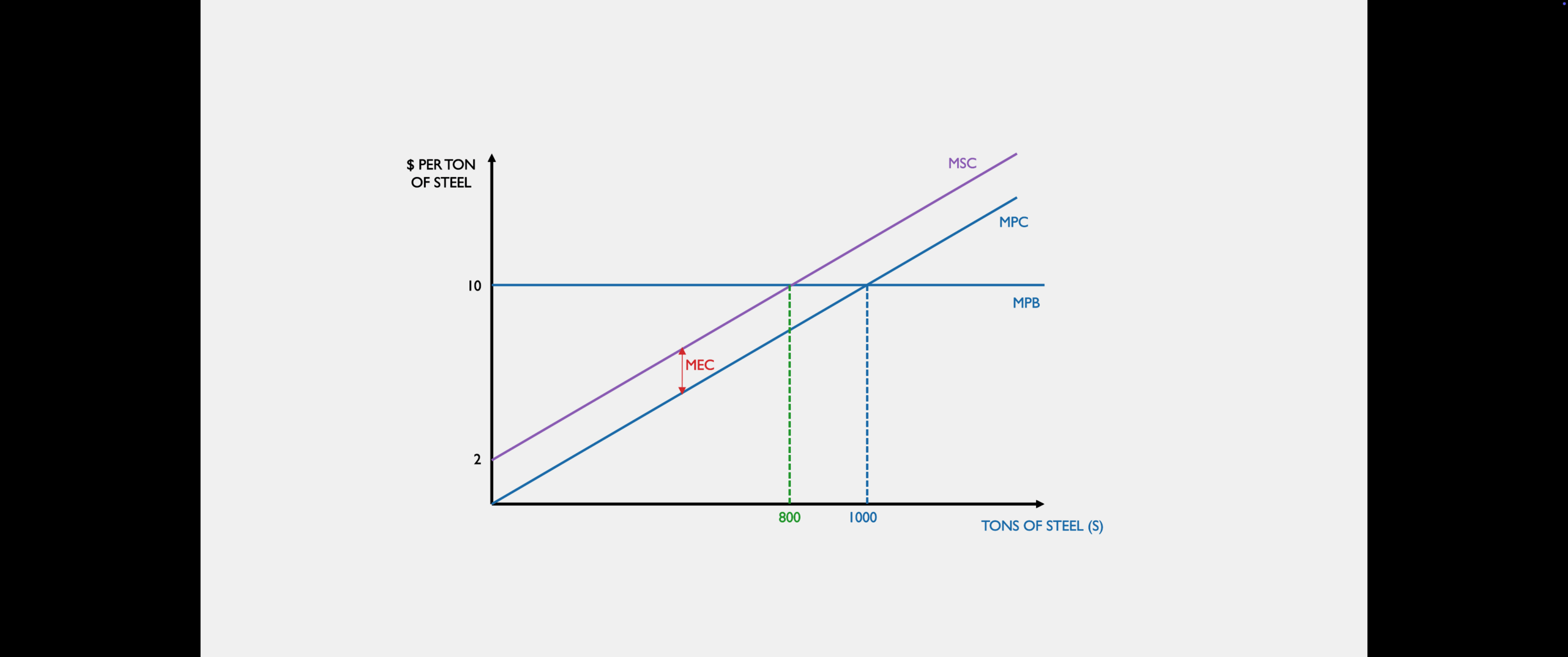

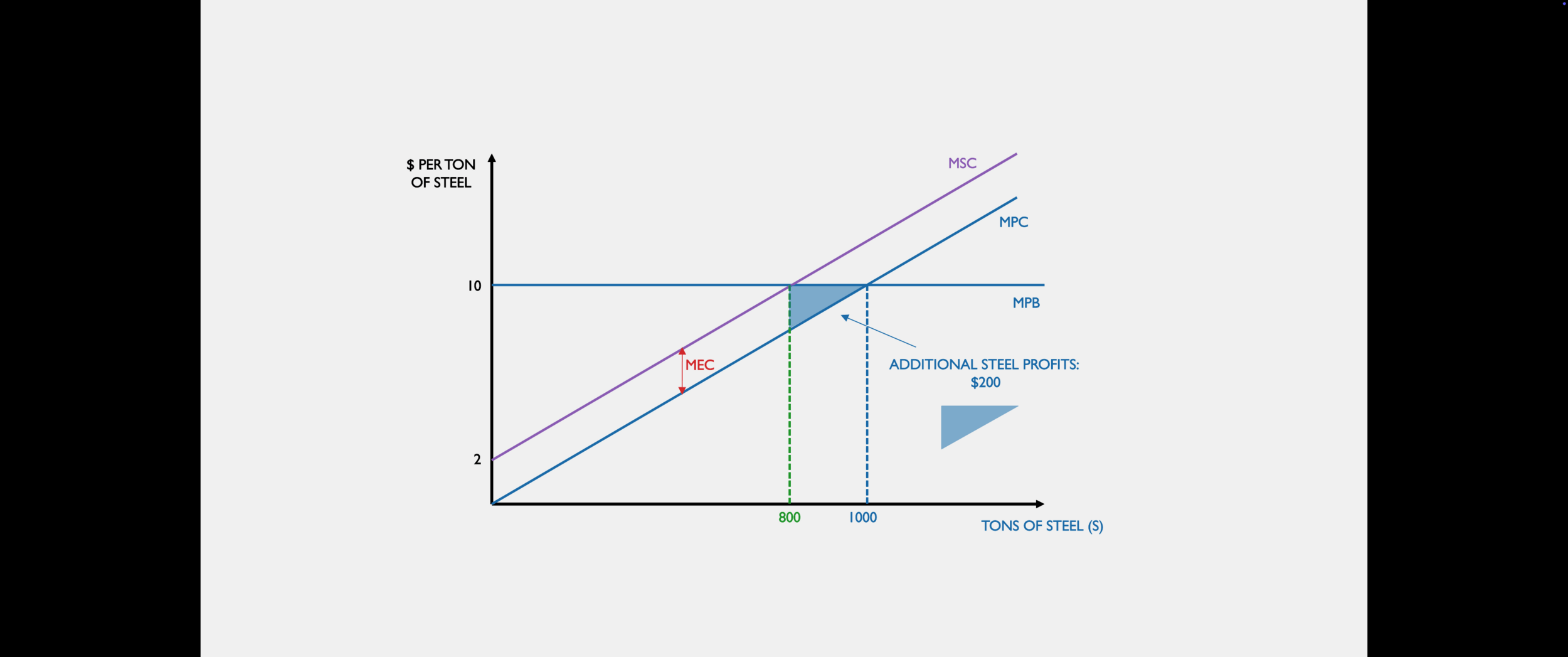

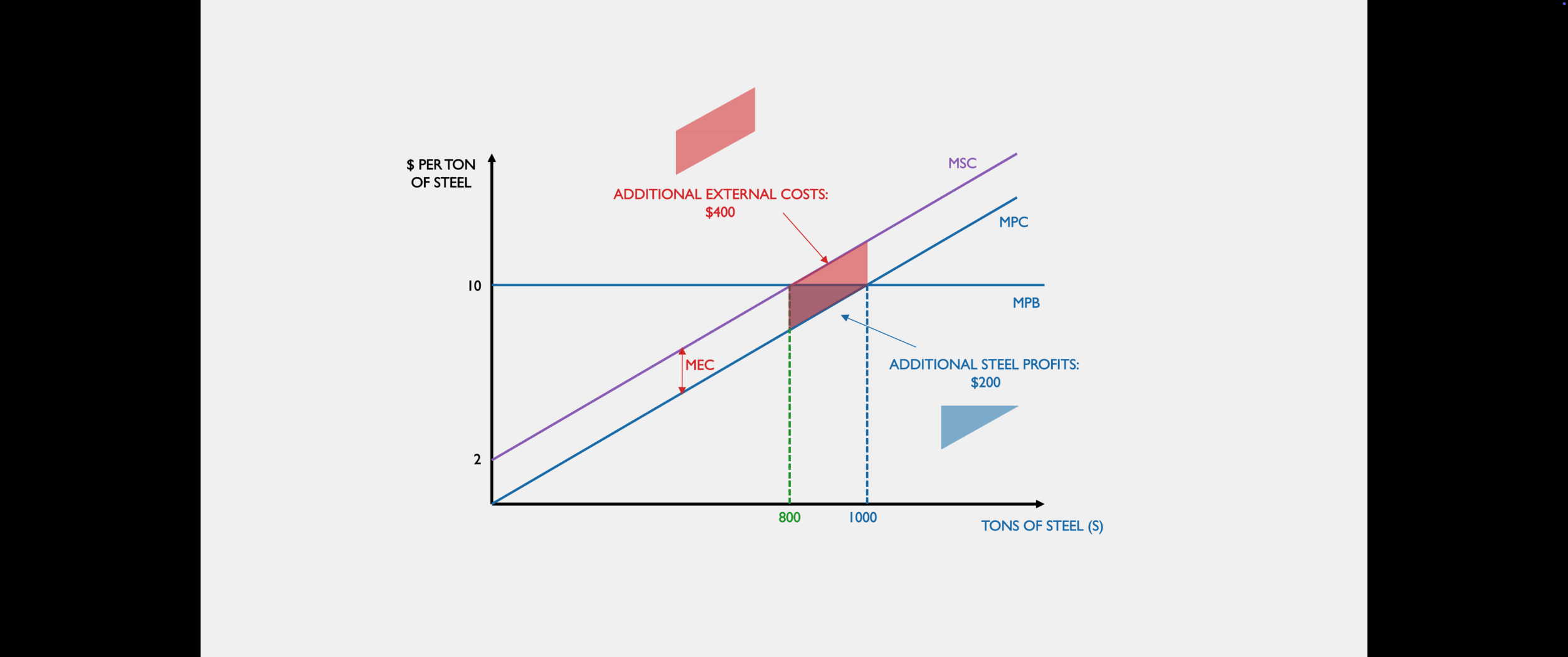

Production Externalities

- Individuals solving their own optimization problem

disregard the external effects they have on others - Marginal social cost (MSC) = marginal private cost (MPC) + marginal external cost (MEC)

- Market equilibrium will occur where MB = MPC

- Social optimum is where MB = SMC

Note: I'm trying to switch from "private marginal cost (PMC)" and "social marginal cost (SMC)" to "marginal private cost (MPC)" and "marginal social cost (MSC)" ... in the meantime I'm super inconsistent. You can use either, and you'll see both used in this presentation.

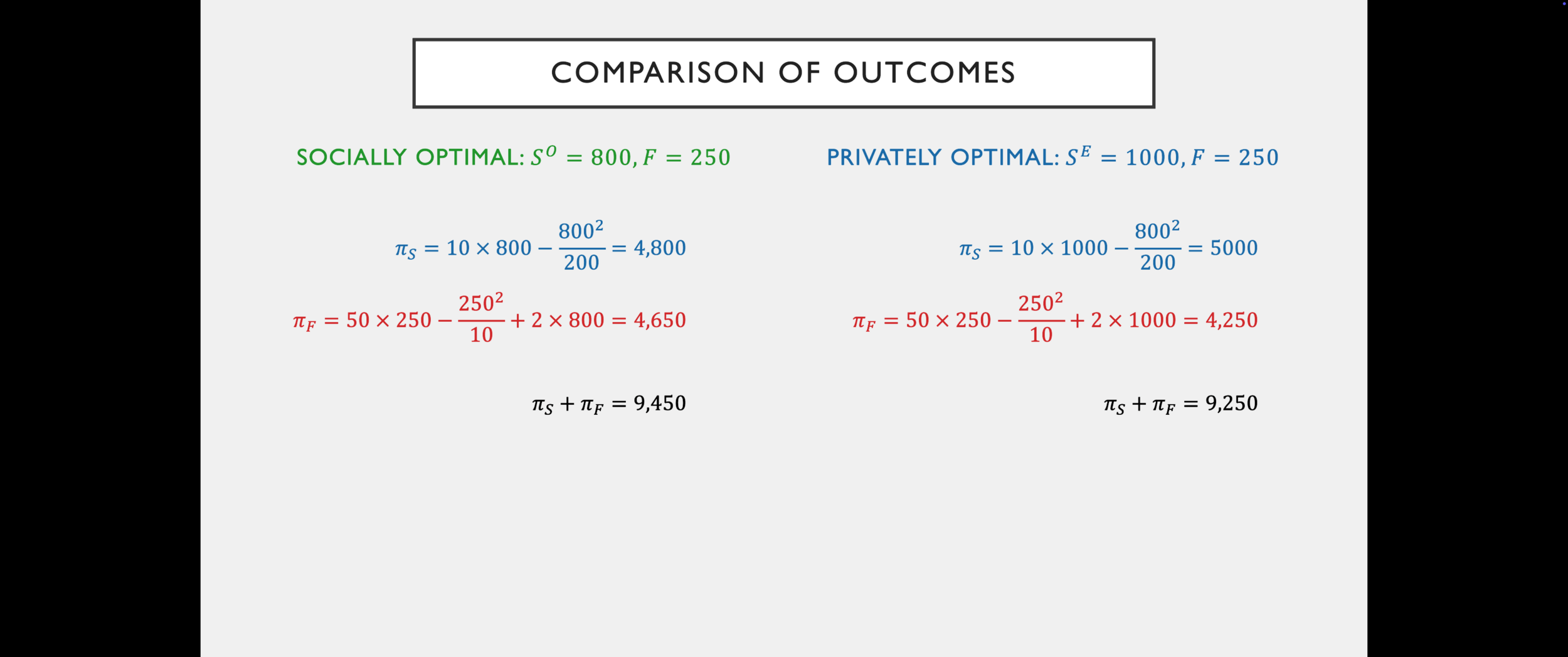

Steel Mill and Fishery

Base Model: Profit Maximization

Extension: Production choices affect other's profit

Conflict: Steel mill only takes into account its own cost,

not impact on the fishery.

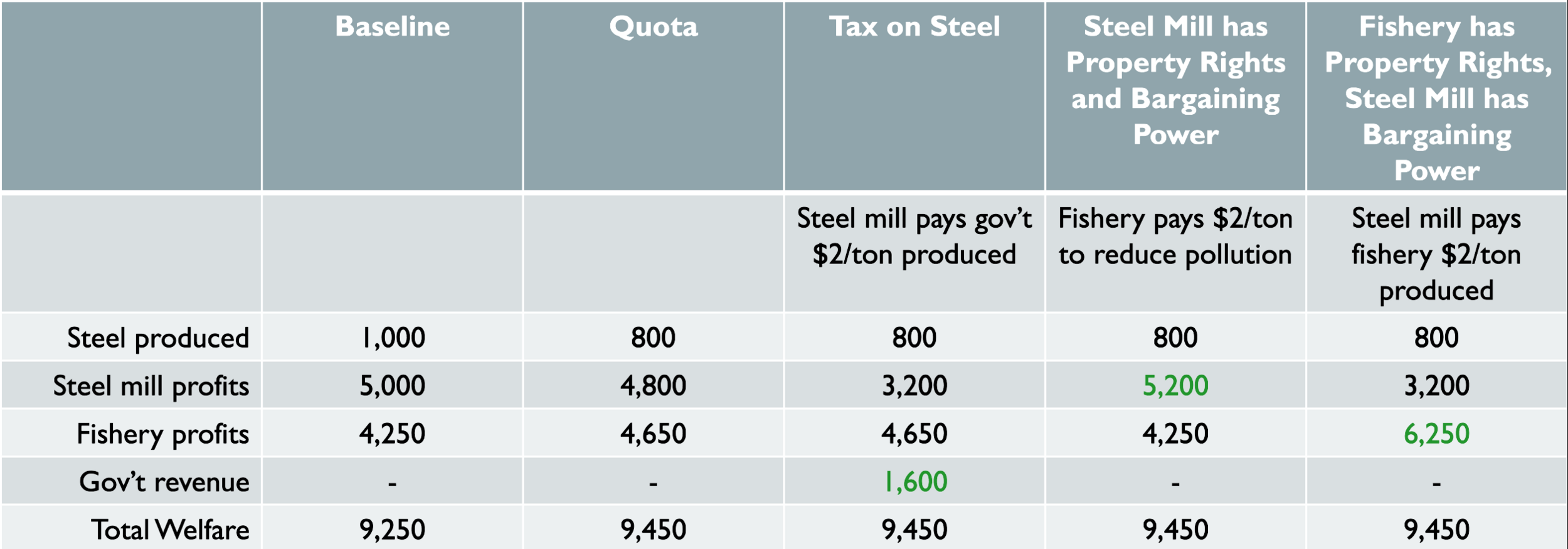

Who does better under each scenario?

Which scenario is overall more profitable?

How can we get the steel mill to produce the socially optimal amount?

- Government solutions

(imposed by a third party) - Negotiated solutions

(achieved by the agents themselves)

[ GOVERNMENT SOLUTIONS ]

Policy I: Direct regulation

Dictate that the firm must produce

exactly 800 units of steel.

- Good if the government knows exactly how much is optimal

- Not so good otherwise

[ GOVERNMENT SOLUTIONS ]

Policy II: Impose a "Pigovian tax" equal to the amount of the negative externality.

- Good if the government knows exactly how much damage producing steel occurs

- Not so good otherwise

[ PRIVATE SOLUTIONS ]

Ronald Coase's insight: we can achieve the optimal quantity via negotiation if we assign property rights to the firms.

- Give the steel mill the "right to pollute" and let the fishery pay them to not pollute.

- Give the fishery the "right to clean water" and let the steel mill pay them to pollute.

Coase Theorem

Absent "transaction costs,"

private bargaining reaches the efficient outcome,

for any allocation of initial property rights.

Possible "transaction costs"

Costs of measuring/contracting on the relevant externalities

Incentives for each agent to pretend that the costs are greater than they are

Lawyers' fees

Monitoring

Comparison of outcomes

The allocation of property rights doesn't affect the amount of steel produced...

but it does determine winners and losers!

Market Externalities

What happens when there are too many people to contract?

Pigovian tax:

Internalize the externality so that private marginal cost equals social marginal cost.

Competitive equilibrium:

consumers set \(P = MB\),

producers set \(P = PMC \Rightarrow MB = PMC\)

With a tax: consumers set \(P = MB\),

producers set \(P - t = PMC\)

Problems and Complications

- What if not all firms generate the same externality?

- Some firms will be overtaxed, others undertaxed

- No incentive to switch to less polluting production processes

- Better solution, if possible: measure and tax the externality itself

(tax on pollution/emissions), not the good that generates it as a byproduct- Carbon tax vs. steel tax

- Tradeable pollution quotas ("cap and trade") incentivize cost minimization and innovation

An Interesting Twist

- Competitive markets: all firms set P = PMC, so in equilibrium MB = PMC.

- Market power (e.g. monopoly): firms charge P > PMC and underproduce relative to the free market.

- In the presence of externalities, having firms with market power can be welfare improving.

- This could be an interesting final exam question...

Q: Makler, what do you think about taxes?

A:

It depends. What model are we in?

Conclusion: Externalities

In the presence of externalities, personal decisions affect others.

If everyone just balances their own personal marginal benefits and costs,

it can have a negative (or positive) external effect on others.

Markets will not, in general, result in a Pareto efficient outcome on their own — there is a role for government intervention.

Broader conclusion: markets don't always result in the optimal result; but understanding the market mechanism can allow you to shape public policy that gets closer.

Econ 50 | Spring 25 | Lecture 23

By Chris Makler

Econ 50 | Spring 25 | Lecture 23

- 584