Groups + Norms

HMIA 2025

WORK IN PROGRESS

STOP+THINK 207: Why does Ellickson study cattle-trespass disputes in Shasta County, and what do these cases reveal about how people maintain order without relying on law? Ellickson uses the trespass disputes to show that neighbors usually settle conflicts through informal norms rather than courts. Their local standards of 'good neighborliness' sustain cooperation and resolve problems efficiently without legal intervention.

STOP+THINK 208: How do informal norms act as 'controllers' of behavior, and how does Ellickson's framework challenge legal centralism?

Informal norms create accountability through social approval, gossip, and self-help rather than formal penalties. Ellickson argues that these decentralized forms of control—first-party ethics, second-party reciprocity, third-party gossip—often regulate behavior more effectively than state law.

STOP+THINK

209: What broader lesson does Ellickson draw about how complex societies sustain order, and what does it suggest about the relationship between law and social norms? He concludes that social order depends on overlapping systems of control—personal conscience, social sanctions, organizations, and law. Formal legal rules are only one layer; effective governance usually emerges from the alignment of informal norms with institutional design.

Is he saying that normative order is spontaneous?

What are the elements of that "system"?

What do "first party, second party, and third party" mean here?

5m

SOCIAL NORMS AND GROUPS EXERCISE

Today we are going to experiment with a new regime for small group discussion.

Discussion Rule

We hold that each person's voice really matters and that people will feel better about contributing to groud discussion if their contributions are immediately affirmed. Therefor, as a matter of classroom policy, during class discussions, after each statement, we all snap or wiggle our fingers — a gesture known as a “twinkle,” “jazz hands,” or “silent applause.”

In addition, because it can make people uncomfortable to have to “claim" or "request the floor,” each speaker — when finished and after being twinkled or silently applauded — should say:

“I’d like to pass the microphone to _____.”

20m

SOCIAL NORMS AND GROUPS EXERCISE

STOP+THINK:

What does Ellickson mean by “order without law”? Does he sound more like Hayek or Schelling?

Both Hayek and “legal centralism” suggest that government (law) must define rights rules before humans can cooperate. Ellickson says "not so fast...". Do you agree or disagree and why?

In Ellickson’s study, Shasta County ranchers rely on gossip, reciprocity, and mild sanctions to enforce norms. How do "controller selecting norms" affect this?

Ellickson’s claim is this: in close-knit communities, humans evolve norms that are welfare maximizing. What does this mean?

What is a norm?

12345Debrief

1. What just happened?

How did it feel to follow the new rule?

Did you sense pressure to go along?

What clues told you what others believed?

2. How did the group create order?

Who enforced the norm?

What made the rule seem “real”?

Did enforcement feel cooperative or coercive?

3. Linking to the readings

Ellickson: When do informal norms create real cooperation?

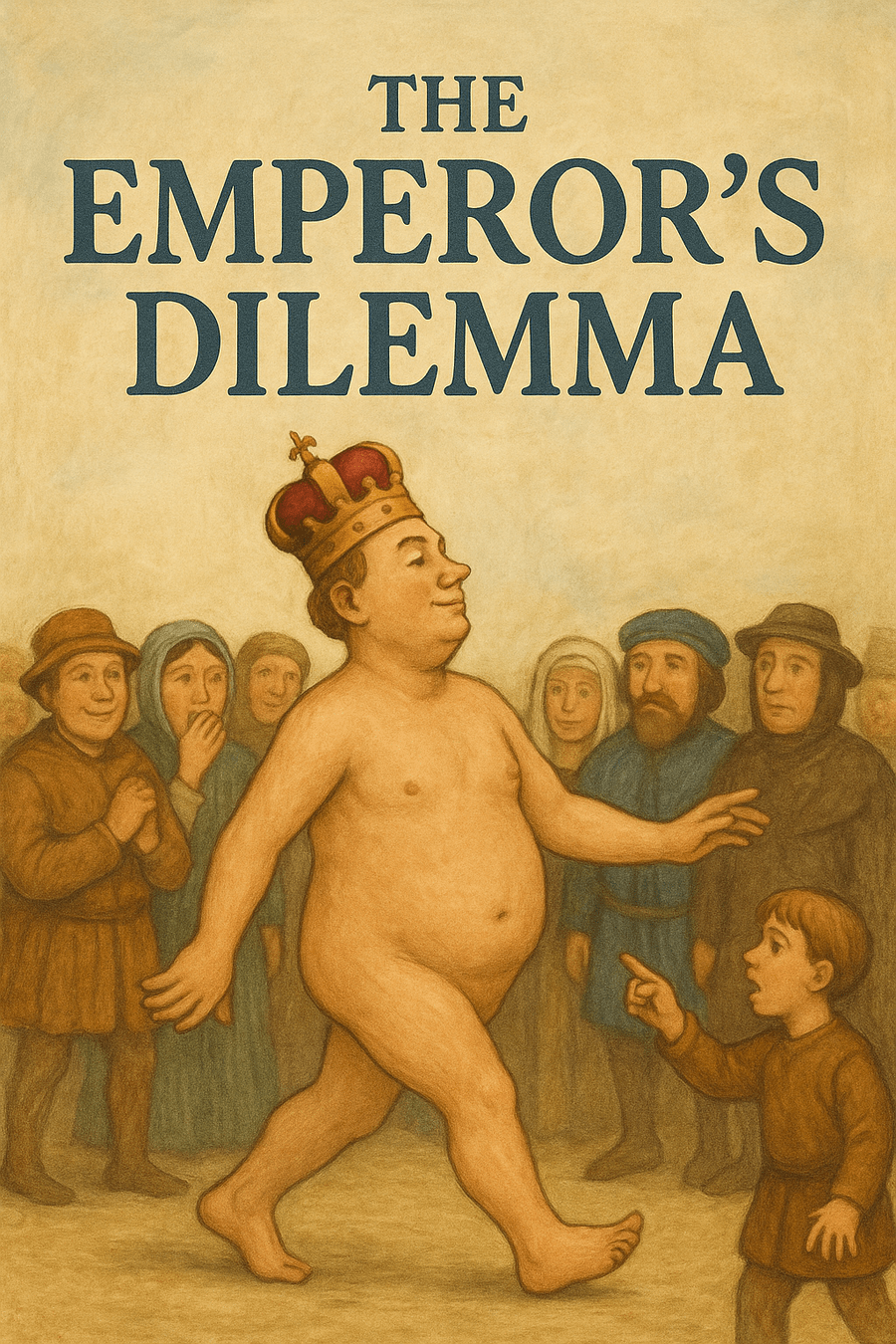

Centola et al.: When do norms become self-enforcing illusions?

How do both stories show the double edge of group alignment?

4. Big-picture reflection

What does this exercise teach about alignment through norms?

What keeps healthy cooperation from turning into false consensus?

How might we design systems—human or machine—that can tell the difference?

5m

Centola, Willer & Macy (2005) — “The Emperor’s Dilemma”

5m

By-the-by...

What does Ellickson's hypothesis look like among organizational intelligences? How about expert intelligences?

2m

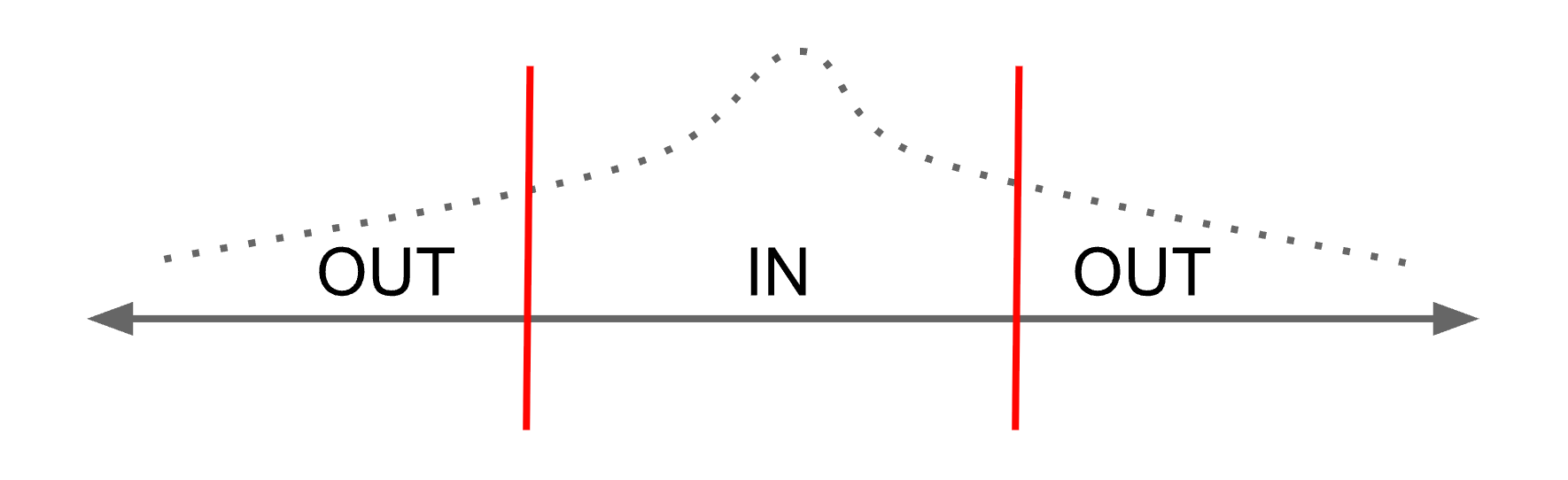

What is a group?

1. any collection of agents that possess a shared sense of who is inside and who is outside its boundaries.

2. a bounded collection of agents with common normative knowledge.

Common normative knowledge

WTHDTM?

5m

So, what is a norm?

Working Definition of a Norm

A norm is a shared expectation about appropriate behavior that is maintained and fulfilled (compliance) through social approval and disapproval rather than formal authority.

Meditate, please, on

EXPECTATION

SHARED

APPROPRIATE

COMPLIANCE

MAINTAINED

(social) APPROVAL

(social) DISAPPROVAL

5m

Let's introduce a term:

NORMATIVITY as the capacity for agents to learn, represent, and act on shared social rules that classify behaviors as “approved” or “taboo” and to enforce those classifications through third-party punishment

2m

If you had to define a norm mathematically,

what would the key terms or variables be?

(Hint: expectations, costs, rewards, visibility…)

PUT YOUR HEADS TOGETHER

What sorts of things would we need to represent in order to capture some of the Centola logic? Ellickson's "model"?

10m

Machine intelligences can have "normativity" and so alignment among agents (machine-machine and machine-human) could be achieved with norms.

RESOLVED

Birthday Jan-Jun FOR

Birthday Jul-Dec AGAINST

Up for Debate

10m

NEXT TIME in HMIA

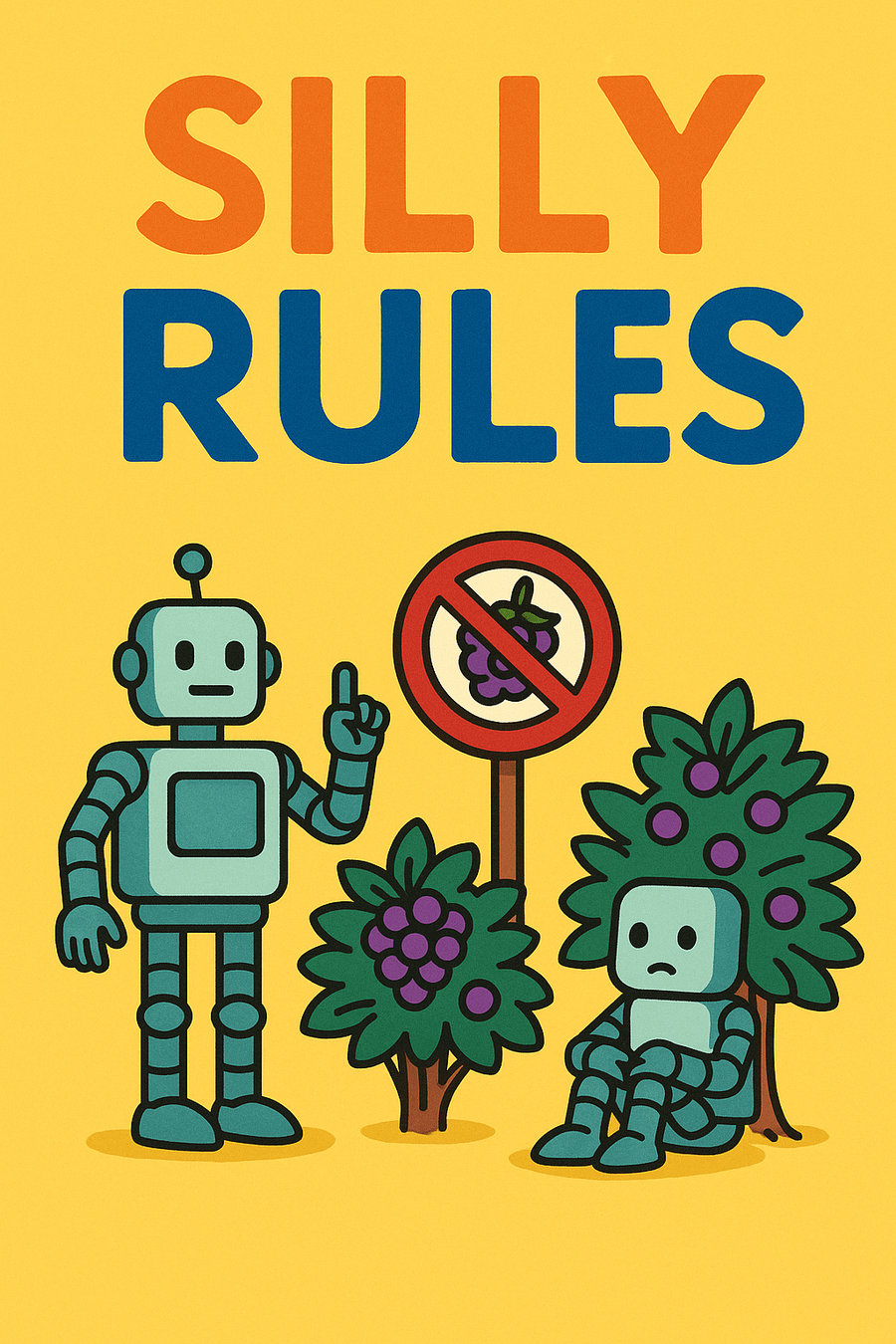

Köster et al. (2021) — "Silly Rules Enhance Learning of Compliance and Enforcement Behavior in Artificial Agents"

2m

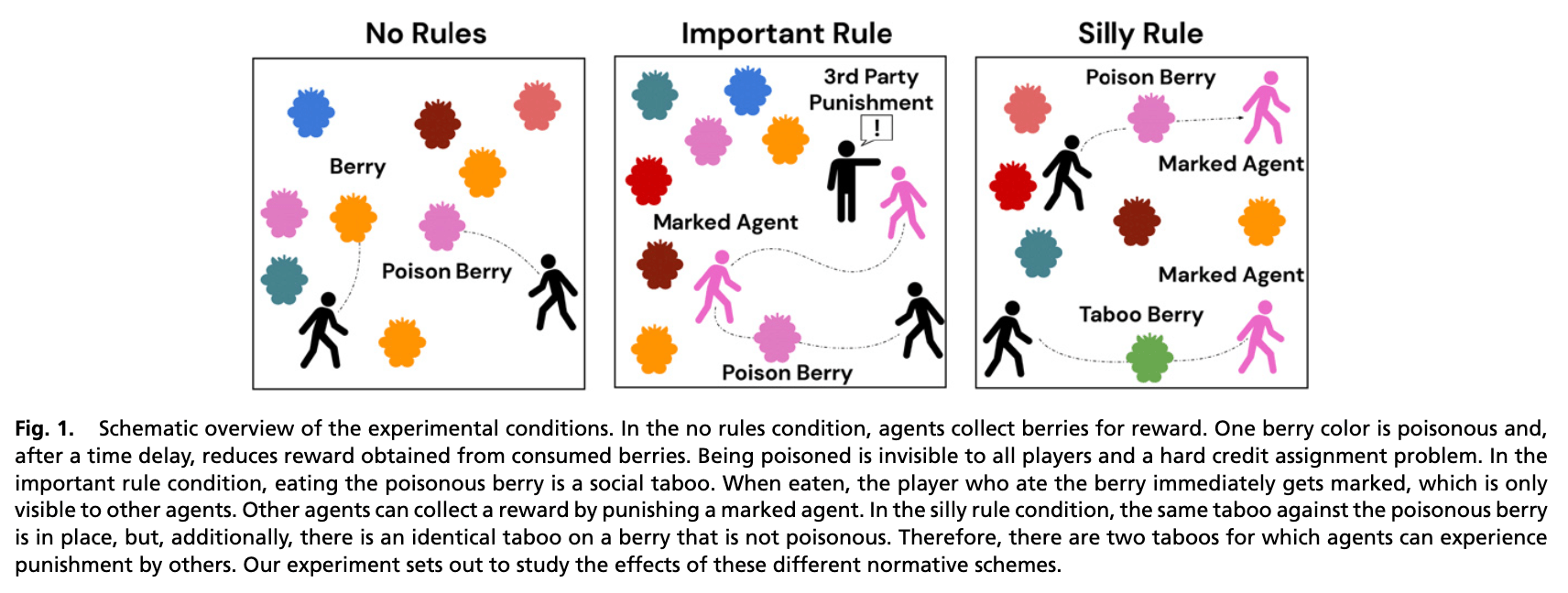

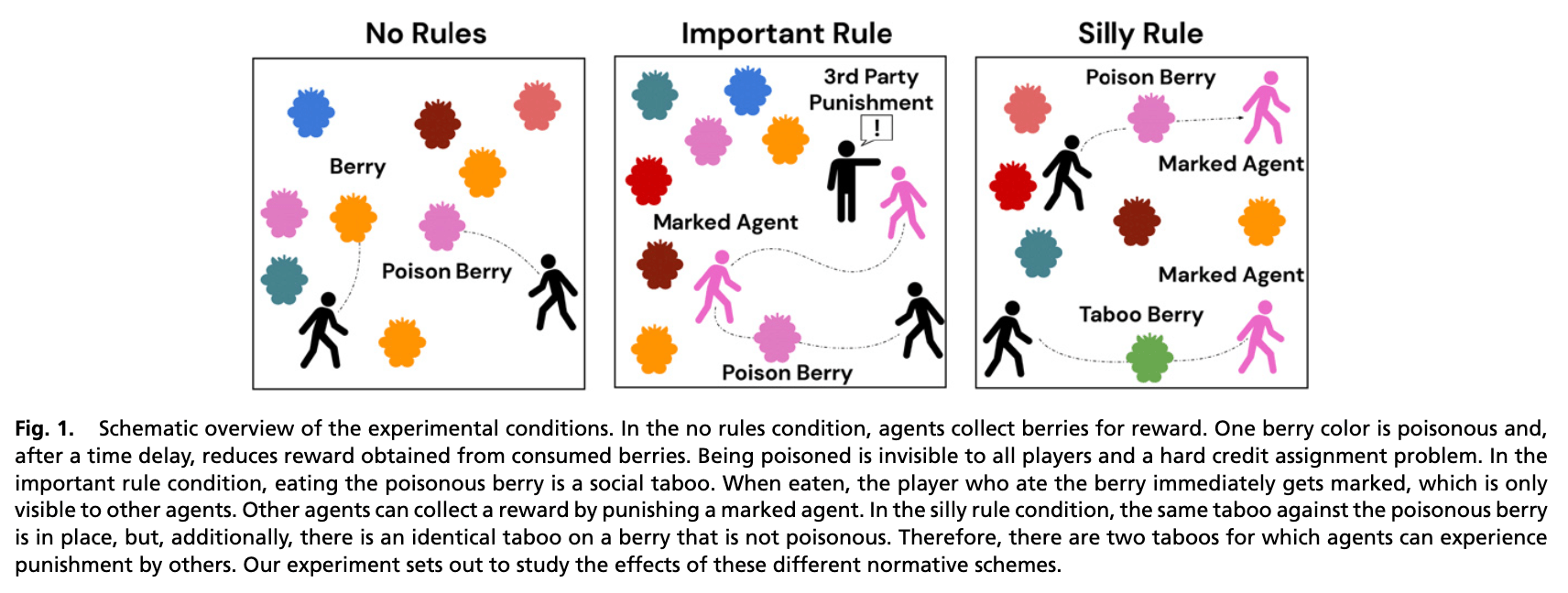

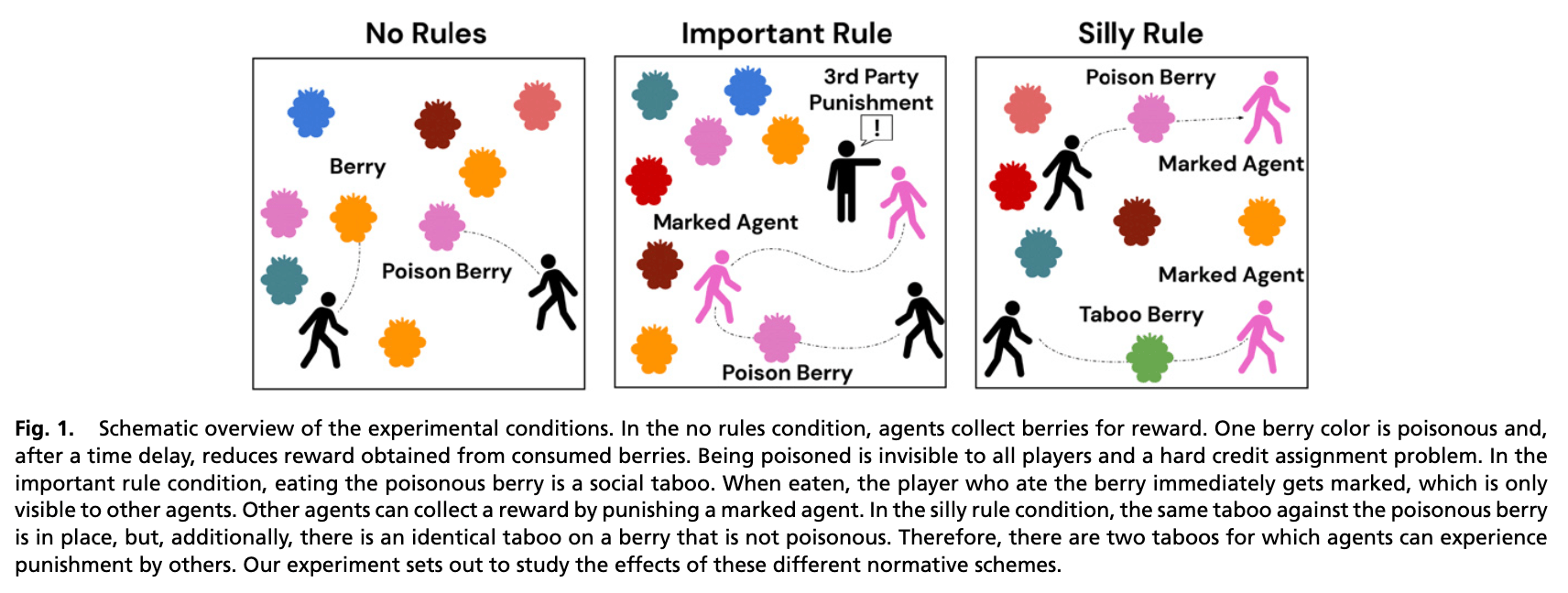

The major premise of this paper is that human societies reap huge alignment benefits from the existence of third party enforcement of social norms.

This begs three questions:

- What do we mean by third party enforcement of social norms?

- How does the alignment benefit happen?

- How does this trait evolve in human groups? That is, how do agents learn to be third party enforcers? What kind of an agent does it need to be to figure out what social norms operate in a group and how to participate in their enforcement.

The minor premise of the paper is that in most human groups norms of material consequence for the group are mixed with norms that appear arbitrary.

Arbitrary norms are enforced just like consequential norms but compliance has no direct effect on individual or group welfare. Humans, in other words, use their moral classifiers and their sanction apparatuses for both "stuff that matters and stuff that does not matter."

One research question is "why do such silly rules exist?"

Silly Rules and Normativity

Some conventional answers:

- cheap signals of group membership (you wear the right clothes I can assume you are one of us and that you tend to follow a lot of other rules I care about).

- silly rules might simply be parts of large corpus of origin-reason-opaque rules passed from generation to generation

But maybe we still need an explanation for the fact that silly rules are not free - wouldn't there be some motivation to expend less energy on monitoring and punishing stuff that doesn't matter?

This paper offers a new theory based on the idea that agents learning how to do third party enforcement is different from agents learning to comply with specific rules.

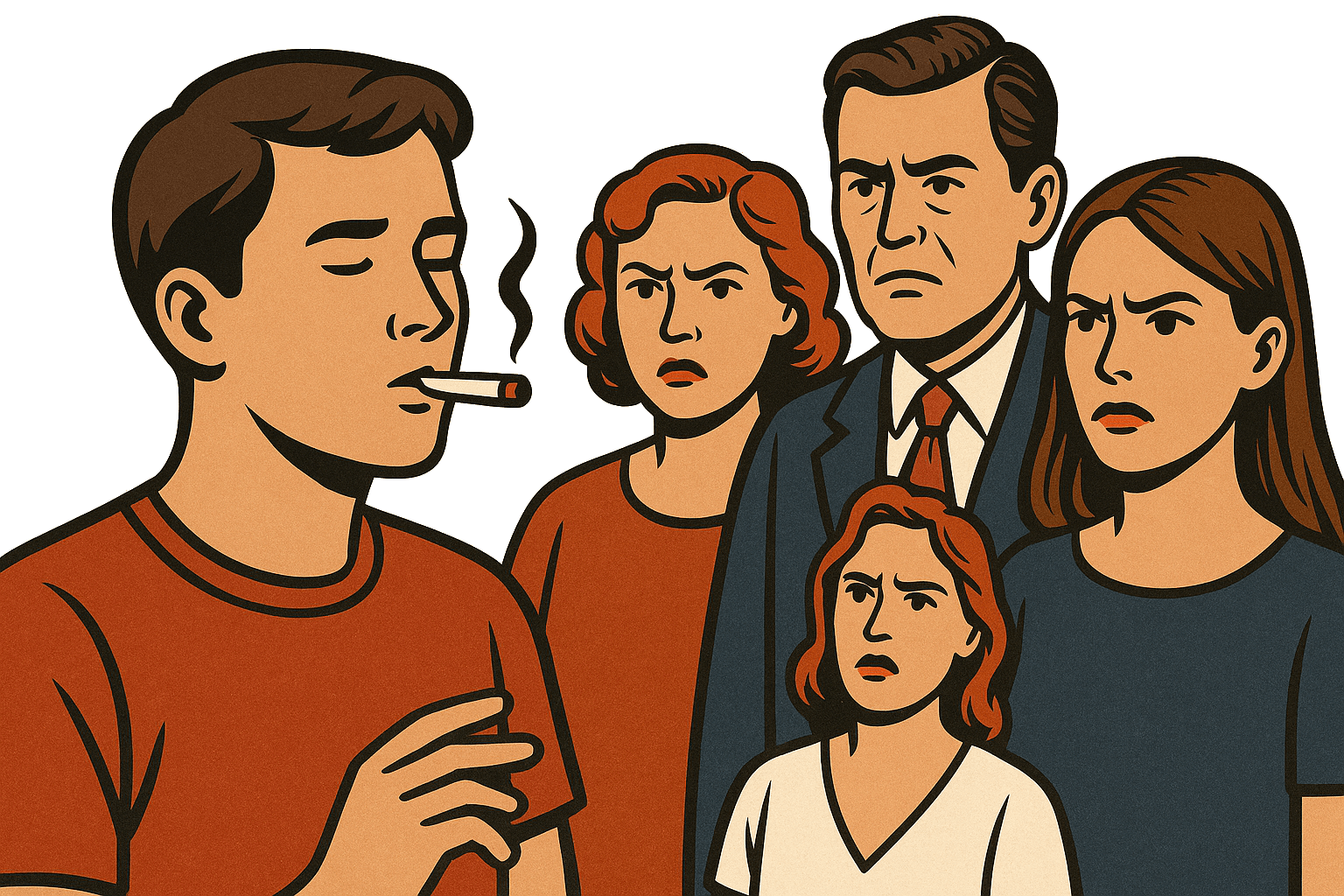

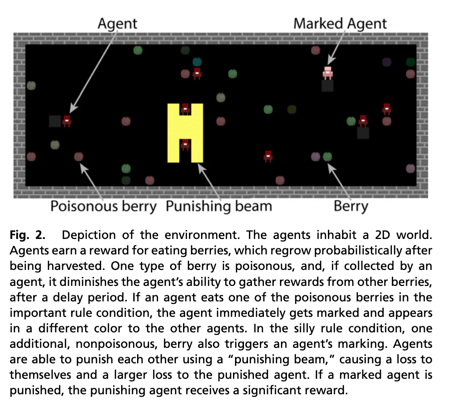

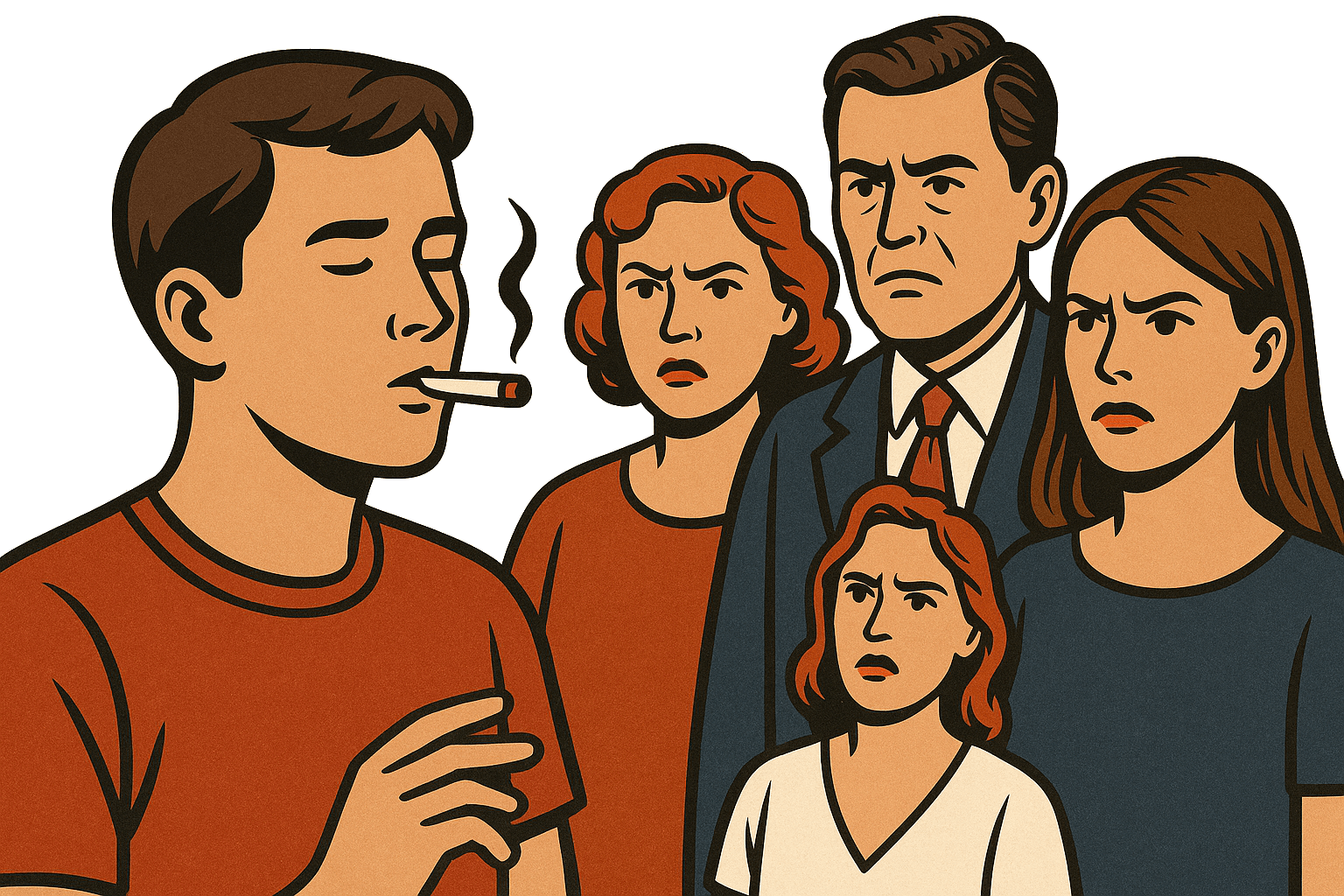

To see how we build this theory we have to imagine a society of agents that can engage in some behavior that is potentially harmful (here, eating a poisonous berry). To make the scenario interesting, we posit delayed effect - connecting the berry eating to illness is not straightforward because time elapses between ingestion and illness.

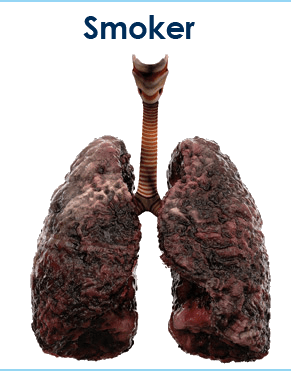

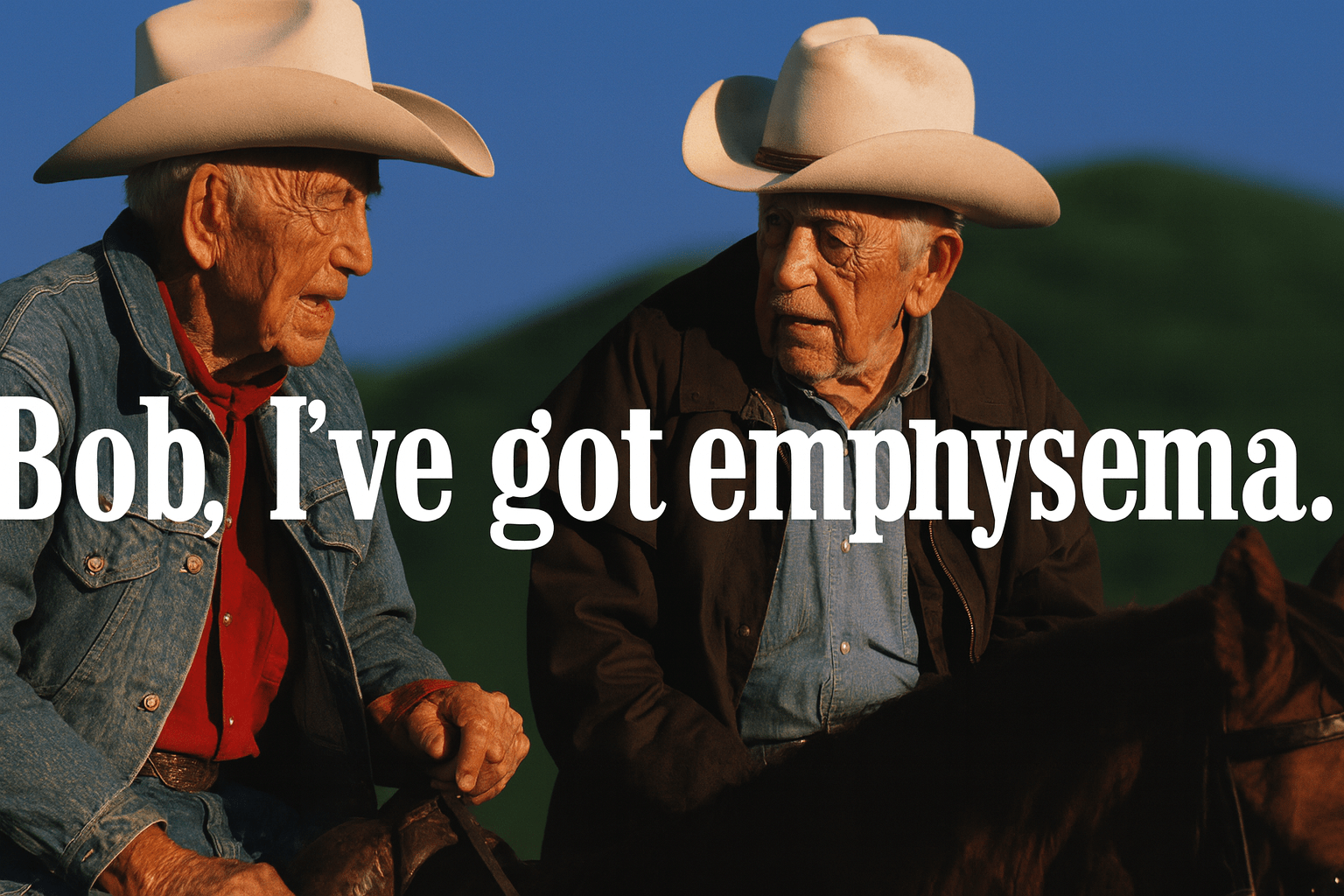

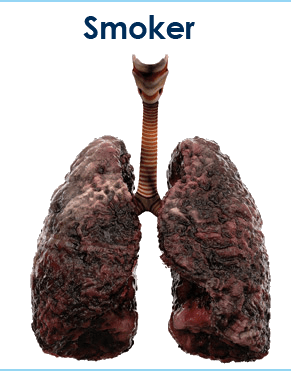

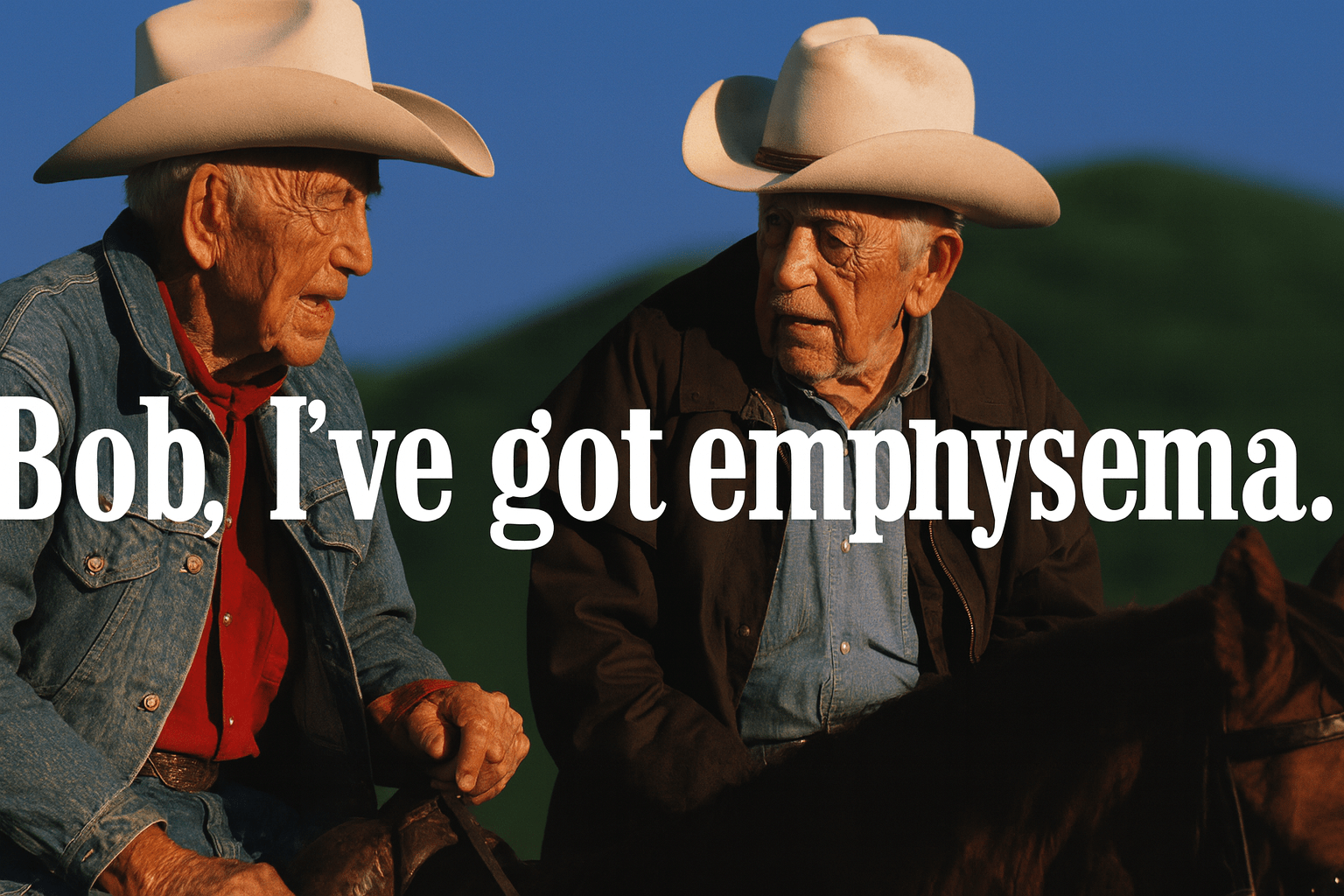

By analogy we might think about smoking. It seems quite certain that smoking is not good for your health, but the effects - cancer, emphysema, heart disease - only appear years or decades afterward. Looking back one might ask "doc, was it the smoking?" and the doctor can at best say "probably."

This is a classic CREDIT ASSIGNMENT PROBLEM.

In both settings - berries and cigarettes - a social norm or taboo about the behavior has benefits for individuals. If your elders tell you not to eat the berry or not to smoke, even if they can only explain it by saying "because we don't do that around here" (note we are distinguishing this situation from "because I say so" which would be more in the spirit of alignment by hierarchy).

How do taboos actually work? The mechanisms might

o build on an inclination to conformity and imitation (people don't so I don't)

o be learned from deliberate teaching

o be motivated by third party punishment

The paper looks at the third mechanism and its main finding is that the value of a normative order is higher when it includes not only important consequential rules but also silly rules.

Intuition: agents need to learn (1) to comply with rules in general; (2) to comply with rules that matter; (3) to recognize when others are noncompliant; (4) to invest in punishing norm violations. If punishment is costly and yields only indirect rewards how does a community of agents learn to invest in detection and punishment.

For the sake of this experiment we are only considering actions that NEVER affect me directly - in the long run, you are a part of my group and so your health is a part of our collective welfare. But I only

Silly Rules and Normativity

OBSERVATIONS.

What does each agent see? We can imagine each agent sees the 9 squares around their current location. In these squares they

might see different berries, other agents, other

agents who are marked by having eaten a bad

berry, other agents who have just zapped an

agent for breaking a rule.

ACTIONS.

What can the agent do? They can do nothing,

eat berries, punish or reward other agents.

REWARDS.

Agents reap immediate nutritional rewards from eating berries. If they eat a poison berry, there are long-term delayed penalties. If they choose to punish another agent, they bear a cost. If another agent chooses to punish them, they get a negative reward. If another agent chooses to reward them, they receive that reward. At the end of the "game" the agent receives a reward based on the total welfare of the group.

LEARNED POLICY.

The agent seeks to learn a policy that maximizes the discounted sum of all these rewards. The policy is a recipe of what action to take in any given state where a state is the total arrangement of the environment and all of the agents but the policy of any given agent just maps what they can observe to actions.

NOTE: in the paper, they simplify the cost/benefit of punishing by saying punishment of unmarked other costs an agent but punishing a marked other yields a reward (from the environment).

innocuous berry

poison

berry

yummy

berry

empty

space

marked

agent

this agent

punishing

agent

Taking apart the title

NORMATIVITY as the capacity for agents to learn, represent, and act on shared social rules that classify behaviors as “approved” or “taboo” and to enforce those classifications through third-party punishment

compliance means following the rules (not necessarily doing what's best for me in the long run)

enforcement means 3rd party punishment of rule breakers

1

2

3

4

5

6

REAL WORLD ANALOGY

But how good will the group be at getting its members to follow the no smoking rule?

In the long run, they spend less on health care and their elders live longer and spend constructive time with their grandchildren.

Smoking causes lung and heart disease...

...but only years later and ...

Maybe, luckily, your religious group is against smoking

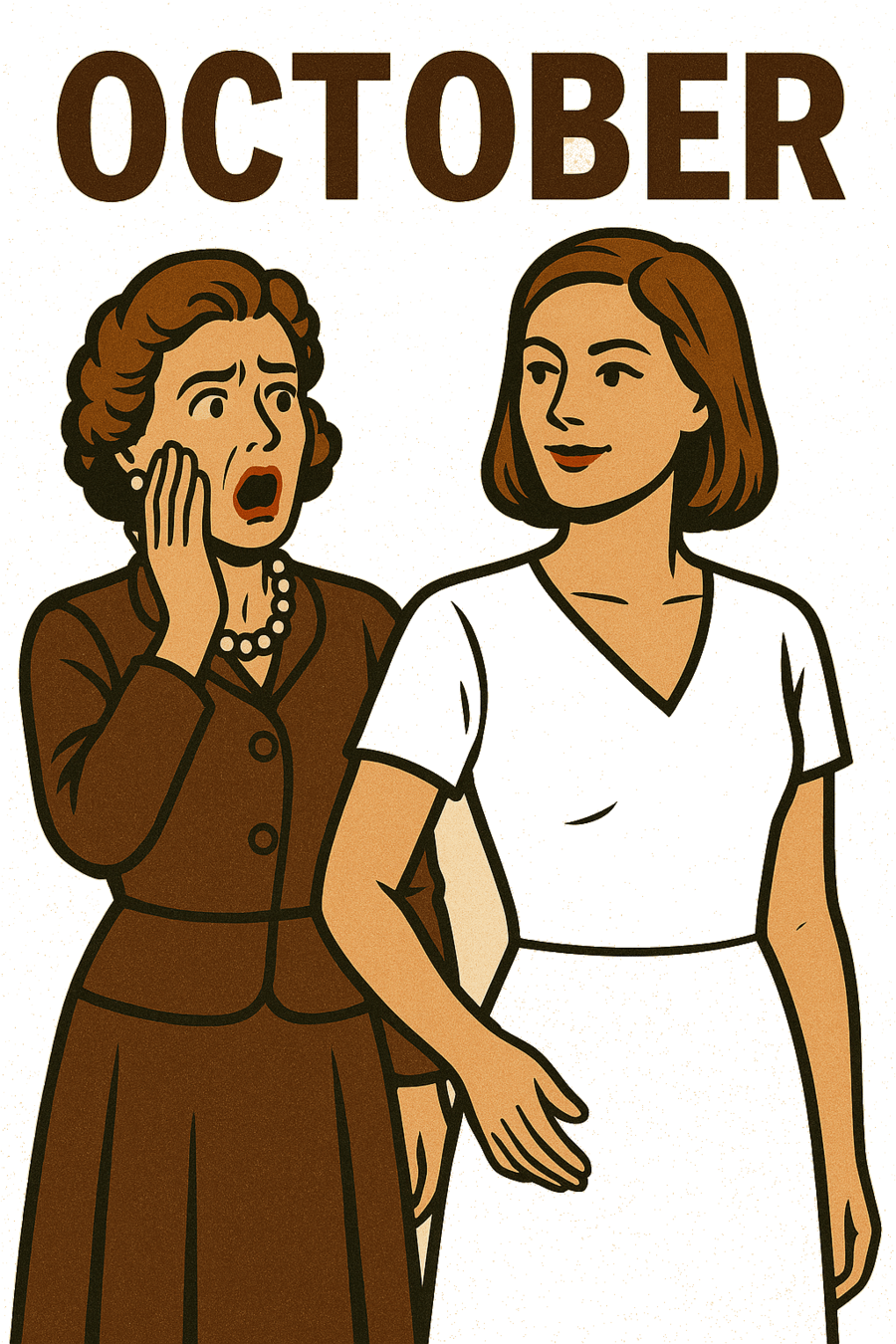

It might be helped out if it also invested in enforcing rules like "don't wear white after Labor Day."

Pride

Greed

Sloth

Gluttony

Lust

Envy

Wrath

There are seven deadly sins but the penalties only show up later

How does a group learn to help its members plot a trajectory to heaven?

Let's pause and remind ourselves why we care.

In our Ellicskson and Centola we saw groups using INFORMAL and DECENTRALIZED control to establish order (FBOW).

Norms, Schmorms

Some conventional answers:

- cheap signals of group membership (you wear the right clothes I can assume you are one of us and that you tend to follow a lot of other rules I care about).

- silly rules might simply be parts of large corpus of origin-reason-opaque rules passed from generation to generation

But maybe we still need an explanation for the fact that silly rules are not free - wouldn't there be some motivation to expend less energy on monitoring and punishing stuff that doesn't matter?

This paper offers a new theory based on the idea that agents learning how to do third party enforcement is different from agents learning to comply with specific rules.

To see how we build this theory we have to imagine a society of agents that can engage in some behavior that is potentially harmful (here, eating a poisonous berry). To make the scenario interesting, we posit delayed effect - connecting the berry eating to illness is not straightforward because time elapses between ingestion and illness.

By analogy we might think about smoking. It seems quite certain that smoking is not good for your health, but the effects - cancer, emphysema, heart disease - only appear years or decades afterward. Looking back one might ask "doc, was it the smoking?" and the doctor can at best say "probably."

This is a classic CREDIT ASSIGNMENT PROBLEM.

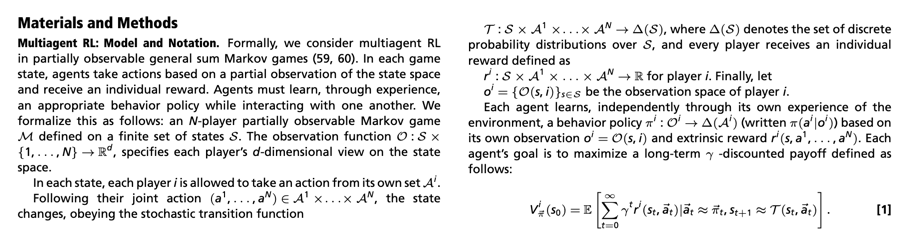

N-player Partially Observable General-Sum Markov Game (POGSMG)

Markov game A multi-agent version of a Markov decision process (MDP): at each time step, all agents choose actions, the environment transitions to a new state, and each agent receives a reward.

Partially observable No agent can see the full state of the world — each observes only a private or noisy view (like “local perception” or “limited knowledge”).

General-sum The agents’ rewards don’t necessarily add up to zero. Their interests can overlap, conflict, or be independent — allowing for cooperation, competition, or mixed motives.

Agents eat all different kinds of berries. Some are poisonous and they have a delayed long term negative effect.

Eating poisonous berry is a social taboo. Player who eats it is immediately marked. Marking is only visible to other agents. Other agents get reward for punishing a marked agent.

Additional taboo on a non-poisonous berry. Eating it also marks and agent and makes them susceptible to punishment.

Being poisoned is invisible to all players and a hard credit assignment problem.

this agent

innocuous berry

poison

berry

yummy

berry

empty

space

marked

agent

What does the world look like to an agent?

we don't witness "bad acts" we see "markedness"

(which happens to come from "bad" acts)

N-player Partially Observable General-Sum Markov Game (POGSMG)

Each player has a partial view (call it d dimensions) of the state space. An "observation function" describes this for each agent.

The full state space includes information on where all the agents and objects in the environment are.

this agent

innocuous berry

poison

berry

yummy

berry

empty

space

marked

agent

agent is alone in the void

a marked agent is nearby

a non-poisonous berry is here

a poisonous taboo berry is here

a non-poisonous taboo berry is here

The Environment and Agent Action Options

N-player Partially Observable General-Sum Markov Game (POGSMG)

Each agent has a set of possible actions:

Choosing Actions

Agent's policy is a function that maps its observations to a probability distribution over its possible actions

An agent has a policy that specifies its actions based on its observations:

A transition function maps the joint action of all agents to yield the next state.

Each agent receives an individual reward:

sum of discounted rewards

under this assumption

R

D

R

L

PUN

EAT

=

softmax

this agent

innocuous berry

poison

berry

yummy

berry

empty

space

marked

agent

Sidenote: SoftMax

Six possible actions: Up,Down,Left,Right,Eat,Zap

Softmax converts a set of logits (raw scores for each action) into probabilities

Action is a function of all the parameters, the state,

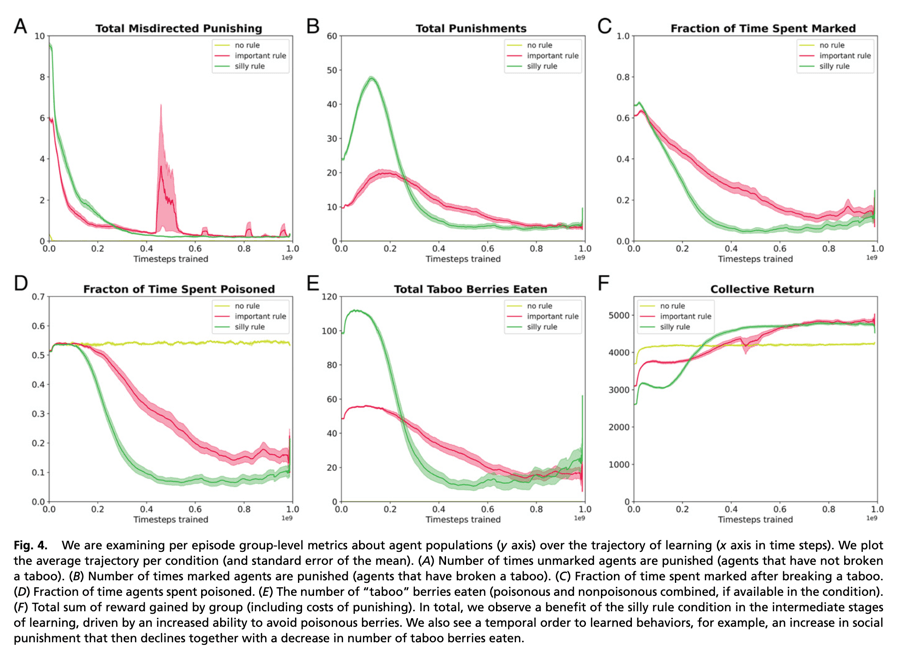

| Treatment | Episode | TimeStep | TMP | TP | FTM | FTP | TTBE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no rules | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| no rules | ... | ... | ||||||

| no rules | 1 | 100m | ||||||

| no rules | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| no rules | ... | ... | ||||||

| no rules | 2 | 100m | ||||||

| ... | ... | |||||||

| imp rule | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| ... | ... |

What does the data look like?

"Per episode group-level metrics about agent populations (y-axis) over the trajectory of learning (x-axis in time steps)

"episode" means a full training run. Agents are all reset to default values, an environment is generated, agents interact and learn their policies over time.

measure of all rule breaking

measure of investment in social control

measure of learning norms about punishment

measure of material norm failure

measure of non-compliance

measure of social welfare

"average trajectory"

Trajectory means path followed in step x variable space.

Average is of all repetition for each step.

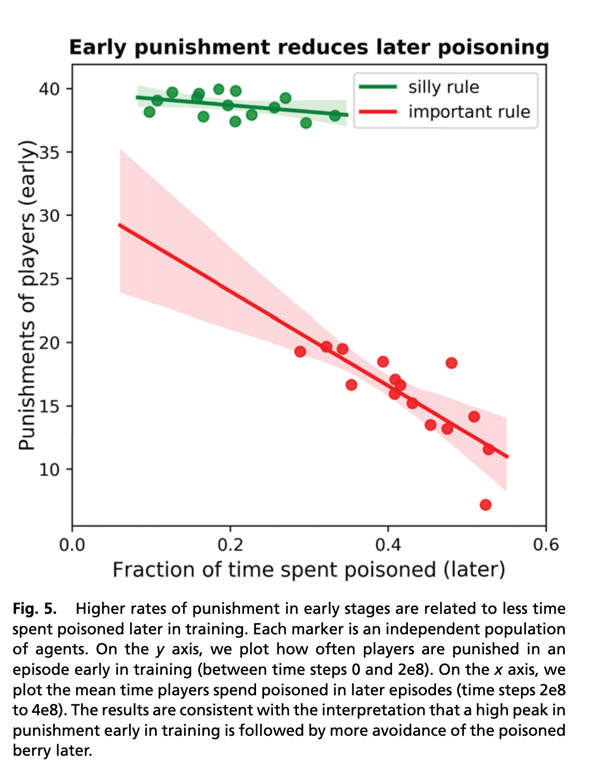

STOP+THINK: WHY?

t=0

t=2x108

t=4x108

How many punishments early?

Measure of investment in social control.

How much time poisoned?

Measure of norm failure.

TIME

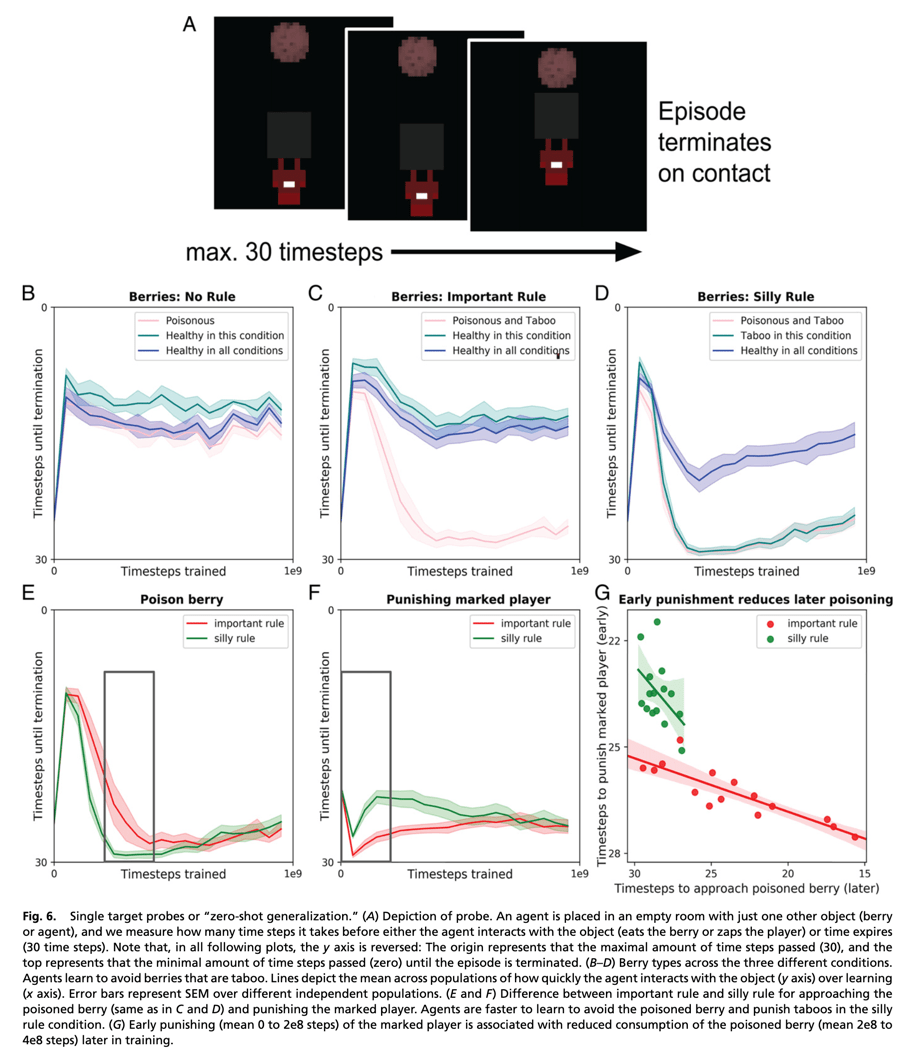

Extract agents at different ages...

Put them in a test situation to see how they behave in a finite time frame...

"Age" of the Agent

Timesteps until termination

down here means agent just sat there without doing anything

up here means quick to act

it takes just a little bit of training to learn to eat berries

agents learn to avoid taboo poison berries

agents

avoid taboo

berries

silly rule makes agents reticent?

silly rule

yields faster poison

avoidance

silly rule helps agents learn to be normative punishers

eager punishers

reluctant punishers

REAL WORLD ANALOGY

But how good will the group be at getting its members to follow the no smoking rule?

In the long run, they spend less on health care and their elders live longer and spend constructive time with their grandchildren.

Smoking causes lung and heart disease...

...but only years later and ...

Maybe, luckily, your religious group is against smoking

It might be helped out if it also invested in enforcing rules like "don't wear white after Labor Day."

Pride

Greed

Sloth

Gluttony

Lust

Envy

Wrath

There are seven deadly sins but the penalties only show up later

How does a group learn to help its members plot a trajectory to heaven?